The Loon Compromise

The years that I have spent here watching fishing birds has shown me that to be very good at one survival task requires sacrificing other powers. Loons, like other fishing birds, have large webbed feet for underwater propulsion. Unlike most birds, its bones are solid and heavy. The compromise: those bones and those feet placed near the tail make the loon a quick diver and endow it with fast submarine propulsion. To fly, however, burns calories fast, and on land its waddling walk is slow and tiring. Also like other fishing birds, to become airborne loons need to run across the water pushing with their legs to become airborne, and only after 10 to 30 meters.

A loon runs into its takeoff, passing a grebe in the background.

Most birds react to danger with flight. The loon almost always dives.

After snorkeling to find fish, the loon begins its dive.

Loons will eat crabs and shrimp as well as fish

Although an occasional loon stays here for summer, most will fly north to the near arctic to breed and lay eggs. In the short northern summer the earlier the hatch the more likely survival. Eggs are kept warm for about one month. Chicks require another 3 months to become strong enough to fly south for winter.

In the arctic the Inuit people, according to National Geographic, kill and eat several thousand loons each season. The Canadian Cree tribe also hunts loons.

The white edges of the body feathers say that this loon is wintering for its first season.

The loon is most famous and loved for its four calls, the most striking of those the wail and the tremolo. The tremolo, a high quavering call, sounds most often across Yaquina Bay in winter and early spring. Like the wail, it too is an alarm and territorial call and a way of locating other loons. We may hear it most often because it also signals an intruder which might be me in a kayak. In the film “On Golden Pond” two quarrelsome elders, Henry Fonda and Katherine Hepburn, have a moment of bliss while paddling their canoe one evening when they hear a pair of loons give the tremolo call. Many writers, like Thoreau, describe loon calls it as a crazy laugh, others as a haunting sad call. Neither fits its place in the loon’s life.

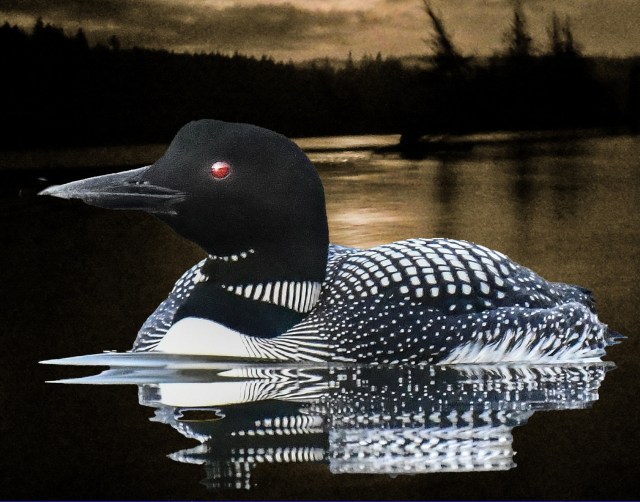

A loon on Yaquina Bay at sunset, my Golden Pond.

A loon on Yaquina Bay at sunset, my Golden Pond.

The sun also rises–two loons prepare to forage on Yaquina Bay.